Not Enough Mines…So Data Mine

James Cormier-Chisholm,

P.Geol., B.Sc. Geology, Env. Dipl., MBA

Owner, Eureka Maps Inc.

Draft Submission to CMJ: Feb 24, 2022

Words 1952

Eureka Map Inc.

Bio : James

Cormier-Chisholm is a Nova Scotia geologist who owns Eureka Maps Inc., a

geological data mining company. He became

interested in data mining after working on the Voisey’s Bay Nickel Project as a

consultant reviewing the mine and refinery complex for the Canadian Federal government

in 1998 to 2000. He worked as a financial writer data mining markets for

Futures Magazine, a US based trade magazine, defined the Exxon Mobil heavy oil

mine resource using data mining techniques, and worked in the environmental

field on megaprojects, including as a fund knowledge worker reviewing financial

and environmental considerations for megaproject funding, underneath Dematteo

Monness. He has actively worked on projects as an environmental manager on

infrastructure megaprojects, and as an environmental EIA reviewer and auditor

consultant one of the world’s largest infrastructure projects with KBR.

email:

jamescormierchisholm@eurekamapincorporated.com

1.

Not Enough Mines…So Data Mine

1.0 Introduction

The world economy needs a massive injection of base metals to enable it to convert from an oil and gas economy to a sustainable economy (See Fig. 1).

Demand

side metal projections are high. BHP estimates copper demand for

battery-powered electrical vehicles (EVs) will need 80 kilograms of copper,

four times as much as an internal-combustion engine. BHP forecasts by 2035

there could be 140m EVs on the road (8% of the global fleet), versus 1 million

today.[i] BHP projects 8.5 million tonnes more

copper needed, a third more copper than today’s total global copper demand.

Nickel demand for EV battery manufacturing projections show growth of 29% per

annum until 2030.[ii] Estimates

show Tesla alone, before we add in all the other automotive companies moving

into electrical vehicles, buying all the output of top producers: Norilsk,

Vale, Jinchuan, Sumitomo, Glencore, and BHP.[iii]

To

enable this mining boom investors and explorationists need a present-day

exploration effort that leverages existing data to increase odds of exploration

success and massively shorten the time required to open new mines.

Inflationary

pressures mean gold and base metal mines will be in strong demand for years to

come. This article illustrates an accurate

data mining approach applicable to finding and developing new metal mines, with

lower upfront costs, reduced risk and time in getting to market.

1.1 Present Situation in Mining

Exploration

Present

mining exploration consists of drilling geophysical anomalies identified by

various geochemistry and geophysical techniques. This current process is slow, expensive, and

risky and is not finding and producing enough mines:

(a) Prospectors & Developers

Association of Canada (PDAC) calculates the odds of finding a mine from exploration

to mine(s) commercialization as 0.01%. [iv]

(b) The very low odds of successful

exploration mean mines are harder to find and thus take years to find and

develop with typical quoted time lags for exploration to opening a mine of 15-years. The odds continue to get worse, and the

supply of new mines is plunging. Between 1983 until 2020, there has been a 67%

drop in mines the USA, and between 2011 to 2020, there has been a 32 % drop in

new gold mines, and a 57 % drop in new base metal mines worldwide (See Fig 2

and Fig 3).

1.2 The Horse & Jockey: Geological

Data and Exploration Companies

Industry

and governments approach this exploration time lag issue like a gambler at a

horse race who gathers data about each horse and jockey. The “horses” are various types of geological

data being gathered, and the “jockeys,” are companies with skill levels

to ride a resource race. This horse and

jockey data gathering approach is done to find out what works to find deposits,

and who best finds economic mines. Horses

alone carry the jockeys, but it is horses – the geological data – that win the races.

1.2 Help…It’s Geological Data!

Thousands

of terabytes of data to “help” with a low odds exploration success process is

piling up. Until recently, no one took a look at all this public data, from a

data mining perspective, to find what works and does not work, using a

supercomputer capable of looking and finding economic deposits across vast areas.

Existing

exploration companies take a balkanized exploration approach. Some explore only next to old mines in mining

districts. They anticipate luck will rub

off from those old mining district deposits. Greenfield explorationists have PDAC’s odds. [We have nothing against both approaches

– we wish them well. But this hasn’t

stopped a decrease in new mines (Fig. 1 and 2, previous).

The

Eureka Maps Inc. (Eureka) approach: look for ore deposits both around old

deposits, and in entirely new places, using data mining algorithms that scale to a planetary

level. The Eureka approach presents opportunities

for novel discoveries of ore bodies at a different scale, the planet.

1.4 Crystal Ball

The

techniques include decision tree algorithms, solving both regression and

classification problems to high accuracy levels. Decision Trees create a training model that

predicts the class or value of the target variable by learning simple decision

rules inferred from prior data (training data). Decision Trees, for predicting

a class label for a record start at a root of the tree. Algorithms compare

values of the root attribute with the record’s attribute. On the basis of

comparison, branches corresponding to a value are then added and then jump to

the next node while improving the overall algorithm fit to the dataset. Test confusion matrices are then run on new

known data predicting the accuracy of decision trees. Actual ground truthing by

assay, using various methods, on predicted deposits, then follows, providing a

data miner’s version of geological ground truthing.

Decision

Trees come in two broad flavors:

(1) Categorical and\or binary

decision trees train on a categorical target variable or binary targets, in

our case, economic levels of minable deposits across wide areas of exploration

as these algorithms can handle both various statistical distributions and

ground faults.

(2) Regression algorithm style

decision trees work on continuous grade variables, similar to kriging, i.e.

ore grade changes. Regression algorithms are applicable on specific

ore body statistical distributions within fault boundaries.

Our

approach to wide area exploration focuses most on flavor 1 above. It is an approach developed over many years. Following

an MBA data mining thesis in 1999 on predicting silver commodity markets, we applied financial MARs model results to predict

trade markets for Futures Magazine (For a 500K readership of main market commodities

trader magazine). In 2003, we published a BC Canada, province wide exploration

decision tree data mining prediction result for high production oil and gas

wells in The Oil and Gas Journal.

This was the first time a data mining technique applied to exploration

in geology was published. In 2004, geological

data mining work on Exxon Mobil’s $12.5-billion program revealed three deposits

within a 50 km2 study area.[vi] These deposits today are working

heavy oil sand mine at Kearl Lake, Alberta, Canada. The underground

visualization aspect of work was published in The Oil and Gas Journal in

2008.[vii] In 2020, accuracy of our results placed us in

the top tier out of 2,200 other data mining teams in the South Australia Gawler

Craton government sponsored contest. Between

2020, until present, this approach was scaled up using a supercomputer to

planetary level searches for gold, nickel, and copper metals.

What does the resulting data mined metal classification look like? We concentrate on gold in the next page. First example is a 10 grams per tonne classification for gold in South Nova Scotia, as compared to a simplified geological picture (See Fig. 4). Note, data mining results should be confirmed with follow up ground truthing.[

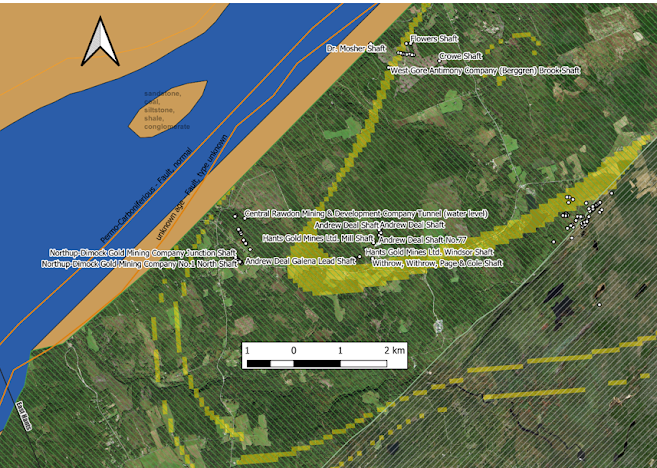

This

approach also works to expand on resource discovery around brownfield

situations, such as the Rawdon Mine, last worked in 1934 (See Fig. 6, next

page).

An interesting point: the data mining algorithm shows a folding rock pattern of ore bodies typically found in quartz in metasedimentary rock of Meguma Group geology which is associated with high grade visible gold in Nova Scotia (Fig. 6). The data mining algorithm has independently discovered a deposit shape at Rawdon Mine that geologists in Nova Scotia are familiar as an observed deposit fold shape that holds visible gold in quartz.

Figure 6 Rawdon Gold Mine

1.5 What to Expect with Better

Exploration Forecasting?

There

will be a much shorter lag time from exploration to commercial mines with the

improved forecasting of deposits. A more accurate method to forecast mines means

much shorter lag times for mine development.

Exploration

programs under traditional methods for base metals have a 15-to-20-year lag

period at 0.01 odds of finding a mine. The lag time is expected to be less than

5-years for prospected resource to mine development for base metal mines, using

a method that gets drilling programs onto the resource quicker, and funding,

when combined with the NI 43-101 process which requires a company to file a

technical report at certain times, prepared in a prescribed format.

Conclusion

To

meet the upcoming sales curves for electrical vehicles, and the conversion of

our mining industry to an industry that can support this oil and gas to battery

economy conversion, we need far more metals.

Supercomputer level data mining across wide areas is Eureka’s way to meet

upcoming metal base metal demand. We

suggest it drops exploration to commercial mine developments for base metals

mines down to under 5 years, rather than a 10-to-15-year development cycle for

exploration to commercial mines.

[i]

Unknow writer, Mining Companies have Dug themselves out of

a Hole, The Economist, Mar 11th, 2017, Edition, found

at:

https://www.economist.com/business/2017/03/11/mining-companies-have-dug-themselves-out-of-a-hole

[ii] Carbon

Intensity Emissions Curve for Nickel Producers, 2021, found at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-americas-electric-vehicle-future/

[iii] Els,

Frik All the Mines Tesla Needs to Build 20 Million Cars a year Mining.com,

Jan. 27, 2021, Found at: https://www.mining.com/all-the-mines-tesla-needs-to-build-20-million-cars-a-year/#:~:text=Tesla's%20models%20use%20on%20average,nickel%20(NCA%20and%20NCM811).

[iv]Prospectors

and Developers of Canada, found at:

https://www.pdac.ca/priorities/access-to-capital

[v]Author

Unknown, Selecting an AutoAI model (Watson Machine Learning),

IBM, found at: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/cloud-paks/cp-data/3.5.0?topic=autoai-selecting-model

[vi] Cormier-Chisholm,

J., C., Sebastian, Gas well development through decision trees,

Oil and Gas Journal, Jan. 20, 2003, found at:

https://www.ogj.com/exploration-development/article/17240107/gas-well-development-through-decision-trees

[vii] Chisholm,

J., Voxel Volumetric Visualization Aids Oil Sands Production Optimization,

found at: https://www.ogj.com/general-interest/companies/article/17218438/voxel-volumetric-visualization-aids-oil-sands-production-optimization

Comments

Post a Comment